Introduction

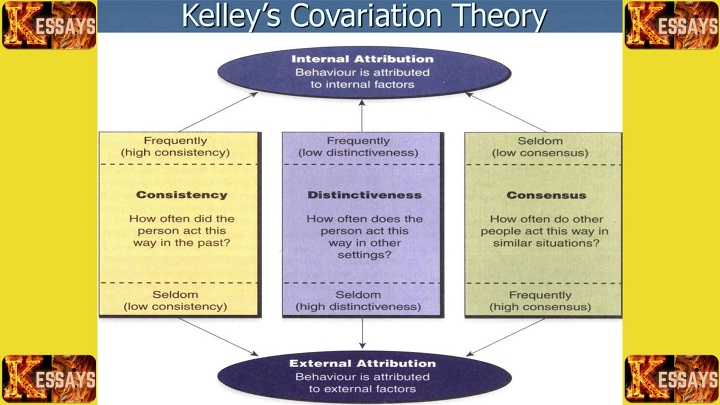

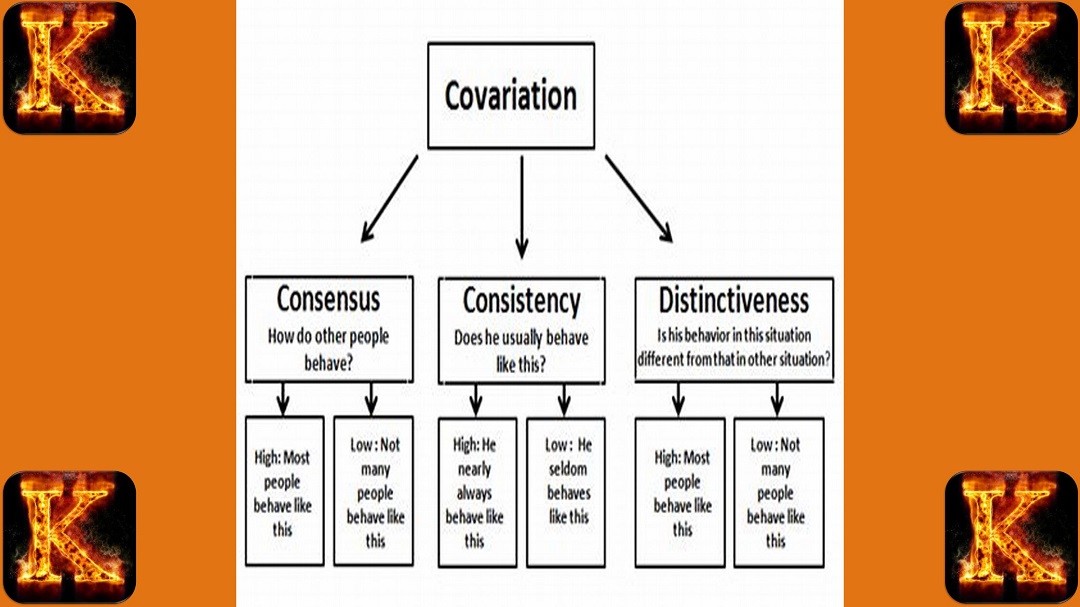

The Covariation Model, a key framework within attribution theory in social psychology, explains how individuals infer the causes of others’ behavior by evaluating patterns across different situations. Introduced by Harold Kelley in the 1960s, the model proposes that people assess behavior using three critical dimensions: consensus (whether others behave similarly in the same situation), distinctiveness (whether the person behaves differently in other contexts), and consistency (whether the behavior occurs repeatedly over time). By analyzing these covariation cues, individuals form internal or external attributions to explain actions. This article illustrates the Covariation Model through a real-life example, demonstrating its application in everyday social judgments and highlighting the cognitive processes involved in understanding human behavior.

The Covariation Model: An Overview

The Covariation Model is a foundational framework within attribution theory, a core area of social psychology that explores how individuals explain the causes of behavior. Developed by Harold Kelley in the 1960s, the model posits that people make causal inferences by systematically observing patterns of behavior across different contexts. According to the covariation principle, individuals use three key types of information—consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency—to determine whether a person’s behavior should be attributed to internal dispositions or external situational factors.

Consensus

Consensus refers to the degree to which other individuals respond in the same way in a given situation. High consensus occurs when many people behave similarly in a particular context, suggesting that the situation may be driving the behavior. For example, if most employees arrive late for a specific morning meeting, there is high consensus, implying a possible external cause. In contrast, low consensus indicates that others do not exhibit the same behavior, making it more likely to be attributed to the individual. If only one employee arrives late while others are consistently punctual, the consensus is low, pointing toward an internal attribution.

Distinctiveness

Distinctiveness evaluates whether an individual's behavior is unique to a specific situation or consistent across a variety of contexts. High distinctiveness suggests that the behavior is context-specific and not typical of the individual in other scenarios. For instance, if an employee is late only for morning meetings but punctual at all other work functions, their behavior shows high distinctiveness—indicating a likely external attribution. Low distinctiveness means the behavior is common across situations (e.g., the employee is late to various events), reinforcing a dispositional explanation.

Consistency

Consistency concerns the regularity of an individual's behavior over time in the same situation. High consistency is evident when a person behaves the same way repeatedly under similar conditions. For example, if the employee is late to every morning meeting across several weeks, their behavior exhibits high consistency. Low consistency, on the other hand, indicates that the behavior fluctuates over time, making it harder to attribute the cause confidently to either internal or external factors.

Making Attributions: Internal vs. External Causes

By analyzing these three dimensions together, individuals form attributions that are either internal (dispositional) or external (situational):

-

Internal Attribution is most likely when consensus is low, distinctiveness is low, and consistency is high. In such cases, the behavior is interpreted as stemming from stable internal characteristics, such as personality traits or attitudes. For example, if an employee is habitually late (high consistency), no one else is late (low consensus), and they are also late in other settings (low distinctiveness), observers are likely to infer that the person lacks time management skills.

-

External Attribution is more likely when consensus is high, distinctiveness is high, and consistency is also high. This pattern suggests that the behavior is driven by situational forces. For instance, if many employees are late for the same meeting (high consensus), and the employee is otherwise punctual (high distinctiveness), yet the lateness is consistent across meetings (high consistency), the cause is likely external—such as heavy traffic or scheduling issues.

Significance in Social Cognition

Understanding the Covariation Model enhances our ability to make accurate and fair attributions in daily life. It underscores the cognitive complexity involved in social perception and helps explain how people weigh multiple cues before drawing conclusions about behavior. By incorporating consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency, individuals can avoid simplistic judgments and instead adopt a more nuanced and evidence-based approach to understanding human actions.

Read Also: The Role of the RNA-PRN in Policy-Making

Example: Covariation Model in a Workplace Scenario

To understand how the Covariation Model operates in practice, consider a workplace scenario involving an employee who frequently arrives late to team meetings. By systematically analyzing consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency, we can identify whether the behavior stems from internal (dispositional) or external (situational) causes—key goals of attribution theory in social psychology.

1. Consensus

Consensus refers to whether other employees behave in the same way in a similar situation. If a large number of team members are also frequently late to the same meetings, there is high consensus. This pattern indicates that situational factors—such as ineffective meeting scheduling, traffic congestion, or organizational culture—may be contributing to the behavior. Thus, an external attribution is more likely.

However, if most employees consistently arrive on time and only one employee is persistently late, there is low consensus. In this case, the lateness is unique to the individual, pointing toward an internal attribution such as poor time management or lack of punctuality.

2. Distinctiveness

Distinctiveness assesses whether the employee’s tardiness is limited to team meetings or occurs across various work contexts. High distinctiveness is evident if the employee is typically punctual for other obligations—such as client meetings, presentations, or one-on-one check-ins—yet consistently late only for team meetings. This suggests the behavior is context-specific and may reflect external factors, such as disengagement with team dynamics or inconvenient scheduling.

Conversely, low distinctiveness means the employee is habitually late across different types of events and situations. This behavioral pattern supports an internal attribution, potentially linked to personal traits like chronic disorganization or low motivation.

3. Consistency

Consistency measures whether the behavior occurs reliably over time in similar situations. If the employee is late to nearly every team meeting, high consistency is present. Depending on the other two dimensions, this could strengthen either an internal or external attribution. High consistency, combined with low consensus and low distinctiveness, typically leads to an internal attribution.

In contrast, low consistency means the employee’s lateness is irregular—perhaps punctual at times and late at others. This inconsistency suggests that the behavior might be caused by temporary situational factors, such as unexpected personal issues, traffic on specific days, or overlapping responsibilities.

Synthesizing the Attribution

By integrating all three dimensions, we can infer the most plausible cause of the behavior:

-

Internal Attribution:

If consensus is low, distinctiveness is low, and consistency is high, the behavior is likely rooted in personal characteristics. For instance, repeated lateness that is unique to one employee and occurs across multiple settings supports the conclusion that the issue lies in the individual’s habits or attitudes. -

External Attribution:

If consensus is high, distinctiveness is high, and consistency is high, the behavior is probably influenced by situational pressures. For example, if many employees are late, the lateness is isolated to team meetings, and the employee is always late to those but not other events, this suggests that something about the team meetings themselves is the problem—possibly their timing, structure, or relevance.

Practical Value

Applying the Covariation Model in workplace analysis allows for more nuanced and evidence-based interpretations of behavior. Rather than jumping to conclusions or making biased assumptions, supervisors and colleagues can evaluate multiple behavioral cues to distinguish between personal responsibility and structural inefficiencies. This leads to fairer performance evaluations, more effective interventions, and improved team dynamics.

Applying the Covariation Model in Everyday Life

The Covariation Model plays a vital role not only in professional environments but also in everyday social contexts. Developed as part of attribution theory in social psychology, the model enables individuals to analyze behavior through three key dimensions: consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. By evaluating these factors, people can determine whether a behavior is best explained by internal traits or external circumstances. This structured approach enhances social perception, reduces cognitive biases, and fosters more empathetic and accurate interpretations of human behavior.

Understanding Consistent Lateness in Social Settings

Consider a friend who is often late to social gatherings. The Covariation Model helps analyze the cause of this behavior by examining how it compares with others and across situations. First, we look at consensus—whether others in the group also tend to arrive late. If most people are punctual and only this friend is consistently late, it reflects low consensus, suggesting that the behavior is likely due to internal factors such as poor time management or a casual attitude toward punctuality.

Next, we examine distinctiveness, or whether the tardiness is specific to social events or occurs in other contexts like work or appointments. If the individual is regularly late across various settings, this indicates low distinctiveness, further pointing to an internal cause. However, if they are punctual in other areas but only late to social events, high distinctiveness suggests that something about those gatherings—such as the group dynamics or timing—may be influencing their behavior.

Finally, consistency evaluates whether the behavior happens regularly over time. If the person is late to nearly every social gathering, high consistency supports the view that the behavior is habitual, again reinforcing internal attribution. In contrast, if lateness occurs sporadically, low consistency implies that external or temporary factors, like traffic or scheduling conflicts, may be at play.

Interpreting Academic Success or Failure

The Covariation Model also offers a structured way to understand academic outcomes, such as why a friend excels or struggles in school. When evaluating consensus, we consider whether other students in the same class perform similarly. If most are doing well or poorly, this reflects high consensus, suggesting that external factors—like an inspiring teacher or a difficult curriculum—may be responsible for the outcome.

The second dimension, distinctiveness, asks whether the individual’s performance varies across different subjects. If the person excels in one subject but struggles in others, it demonstrates high distinctiveness, pointing toward internal factors such as a natural aptitude or interest in that particular area. However, if the student performs similarly across all subjects, low distinctiveness could imply a more general influence, either internal (e.g., motivation) or external (e.g., overall teaching quality).

Consistency further refines the attribution. If the student shows the same level of performance throughout the academic year, this high consistency strengthens the attribution—either internal or external, depending on the other two factors. If performance fluctuates, low consistency indicates the presence of unpredictable or situational variables, such as changing levels of stress or shifting study environments.

Explaining Recurring Mood Swings in Family Dynamics

Another application of the Covariation Model is in understanding emotional behavior, such as recurring mood swings in a family member. To begin with consensus, we ask whether others in the family also experience similar mood fluctuations. If mood swings are common among multiple members, high consensus may point to shared external stressors such as family conflict, financial difficulties, or environmental pressures.

The distinctiveness dimension assesses whether the mood swings are specific to family interactions or occur in other social environments as well. If the behavior is confined to the family setting, this suggests high distinctiveness and may indicate that specific dynamics at home are contributing to the emotional instability. If the mood swings persist across various settings, low distinctiveness suggests that internal factors—such as emotional regulation difficulties or a mental health condition—might be influencing the behavior.

Lastly, consistency looks at whether the behavior occurs repeatedly over time. If the family member exhibits mood swings in most family interactions over a long period, high consistency points toward a stable pattern, which may again support internal attribution. If the behavior is inconsistent, it suggests that external, fluctuating stressors could be responsible.

Enhancing Social Understanding Through Attribution

Applying the Covariation Model to everyday life allows for deeper insights into the reasons behind others’ actions. By systematically evaluating consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency, individuals can make more thoughtful and accurate attributions. This process promotes empathy, reduces attributional bias, and enhances interpersonal relationships by recognizing the complexity of human behavior. Rather than resorting to quick or judgmental conclusions, the model encourages a balanced view that considers both situational context and personal responsibility. In doing so, it equips us to navigate social interactions with greater fairness, sensitivity, and understanding.

Comments are closed!