Introduction

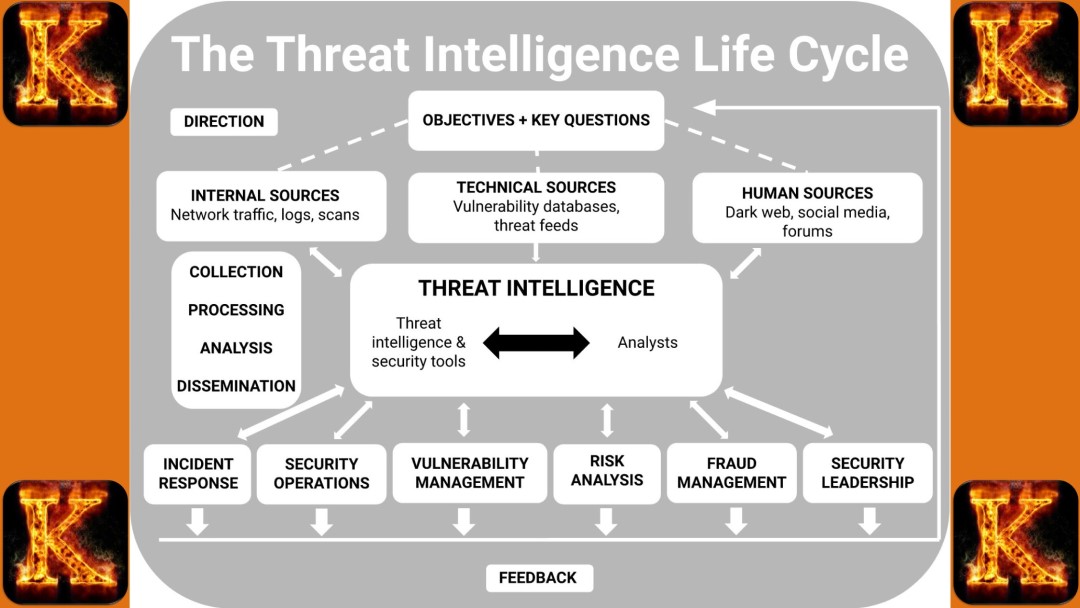

An intelligence collection plan is a structured framework designed to guide the systematic gathering of information and data from diverse sources in order to generate reliable, actionable intelligence. It establishes clear objectives, methodologies, priorities, and timelines, ensuring that collection activities are aligned with the organization’s intelligence requirements.

The central purpose of an intelligence collection plan is to support informed decision-making by delivering accurate, timely, and relevant insights into emerging threats, risks, vulnerabilities, or opportunities. By organizing the collection process, it helps agencies and organizations avoid wasted effort, reduce duplication, and ensure that critical gaps in knowledge are addressed.

In addition, a well-structured collection plan enhances accountability and coordination, as it provides a roadmap that integrates human, technical, and open-source collection methods. It also allows intelligence professionals to adapt to changing operational environments, ensuring that intelligence remains responsive to both immediate and long-term needs. Ultimately, the plan serves as a cornerstone of intelligence operations, bridging the gap between raw information and strategic or operational action.

Understanding the Intelligence Collection Process

Definition and Components of an Intelligence Collection Plan

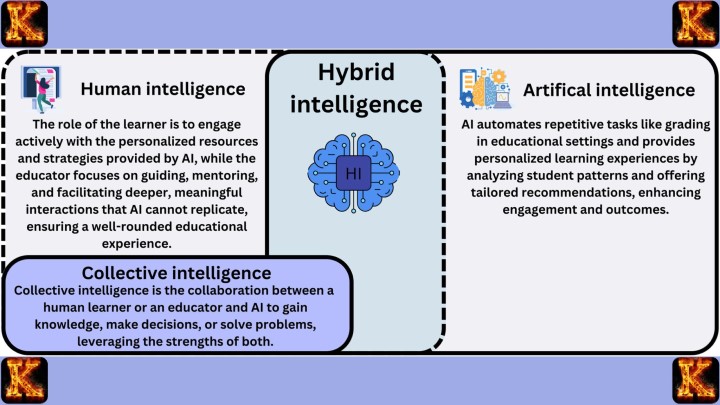

An intelligence collection plan is a structured framework designed to guide the systematic gathering of information. It begins with clearly defined intelligence requirements, which set the objectives and shape the overall direction of the effort. These requirements determine what information is needed and why it matters. To meet them, analysts identify relevant sources of information, ranging from human contacts and open-source data to technical systems and specialized platforms. Once potential sources are established, their credibility and reliability must be evaluated to ensure that the collected material is accurate and trustworthy. The plan also outlines the specific methods and techniques to be used, such as interviews, surveillance, analysis of public data, or technical monitoring, while setting timelines and priorities to reflect the urgency and significance of each requirement.

Importance of Intelligence Collection for Decision-Making

Intelligence collection plays a critical role in supporting decision-making across government agencies, military operations, and private organizations. By providing a detailed understanding of the operating environment, it helps decision-makers anticipate risks, identify opportunities, and respond to emerging threats. Reliable intelligence enables the development of effective strategies and policies, ensuring that choices are based on evidence rather than assumption. In this way, collection efforts form the backbone of informed, proactive decision-making.

Key Principles and Ethical Considerations

Intelligence collection must adhere to key principles and ethical considerations. These include:- Legality: Intelligence collection activities should comply with applicable laws, regulations, and international conventions.

- Privacy and Civil Liberties: Respecting the privacy and civil liberties of individuals and avoiding unnecessary intrusion while collecting information.

- Proportionality: Collecting information that is relevant and necessary to fulfill the intelligence requirements without excessive intrusion or collateral impact on innocent individuals.

- Human Rights: Ensuring that intelligence collection activities do not violate fundamental human rights, including freedom of speech, expression, and association.

Steps in Developing an Intelligence Collection Plan

A. Assessing Intelligence Requirements

The foundation of any intelligence collection plan lies in a clear assessment of intelligence requirements. This involves defining the objectives and identifying the specific information necessary to support sound decision-making. Effective requirements should be precise, relevant to the organization’s priorities, and adaptable to the operational environment. They must also anticipate potential risks, threats, or challenges that decision-makers may face. Without this step, collection efforts risk being unfocused or misaligned with strategic needs.

B. Identifying Sources of Information

Once requirements are established, the next step is to determine where the information can be obtained. Sources may include human assets such as informants, witnesses, or subject-matter experts; open sources like newspapers, scholarly publications, and online platforms; or technical systems such as surveillance equipment, sensors, and satellite platforms. Drawing from a variety of sources enhances the comprehensiveness of the plan and helps reduce dependency on any single stream of information, thereby improving resilience and reliability.

C. Evaluating Source Credibility and Reliability

Since not all sources are equally dependable, rigorous evaluation is essential. Analysts must consider a source’s history, access to information, motivation, and potential biases. For example, a source with privileged access but questionable motives may provide useful but distorted intelligence. Prioritizing credible, consistent, and verifiable sources strengthens the integrity of the overall collection process, ensuring that decision-makers can trust the intelligence provided.

D. Determining Collection Methods and Techniques

After sources have been identified, the appropriate methods and techniques for collection must be chosen. These may include direct approaches such as interviews and debriefings, technical methods such as cyber monitoring or electronic surveillance, or analytical techniques like data mining and satellite imagery interpretation. The selection of methods should be carefully matched to the sensitivity of the requirements, the urgency of the task, and the feasibility of implementation, ensuring both effectiveness and efficiency in the collection effort.

E. Establishing Timelines and Priorities

An effective collection plan also requires the establishment of clear timelines and priorities. Information must be gathered, analyzed, and disseminated within deadlines that match the decision-making cycle. Timeliness can be as critical as accuracy as outdated intelligence may be of little practical value. Prioritization ensures that the most urgent and strategically significant requirements are addressed first, allowing resources to be allocated where they will have the greatest impact.

Read Also: Covariation Model Example: Social Psychology

Types of Intelligence Collection Methods

A. Open Source Intelligence (OSINT)

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) is derived from publicly available sources such as news outlets, social media platforms, academic publications, government reports, and online databases. It is often the most cost-effective form of intelligence collection and provides a broad overview of events, trends, and public sentiment. OSINT can be especially valuable in tracking emerging issues, monitoring geopolitical developments, or validating other forms of intelligence. However, because it is publicly accessible, its reliability must be carefully verified to avoid misinformation or manipulation.

B. Human Intelligence (HUMINT)

Human Intelligence (HUMINT) focuses on information collected from human sources through direct interactions such as interviews, debriefings, interrogations, or long-term agent networks. HUMINT provides unique insights into intentions, plans, and perceptions that are often inaccessible through technical means. It can reveal motivations, organizational culture, or hidden dynamics within groups. While invaluable, HUMINT also presents challenges, including source reliability, potential biases, and the risks involved in recruiting or handling human assets.

C. Signals Intelligence (SIGINT)

Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) involves intercepting and analyzing electronic signals, including communications (COMINT) such as phone calls, emails, or radio traffic, and non-communication signals (ELINT), such as radar emissions. SIGINT can uncover patterns of communication, identify networks, and provide early warning of hostile activities. It often requires advanced interception technologies, decryption tools, and skilled analysts. Because it can yield highly sensitive insights, SIGINT is regarded as one of the most powerful yet technically demanding collection methods.

D. Imagery Intelligence (IMINT)

Imagery Intelligence (IMINT) is obtained through the collection and interpretation of visual data, typically from aerial reconnaissance, satellites, drones, or other imaging platforms. IMINT is particularly effective for monitoring infrastructure, military installations, troop movements, and environmental conditions. Modern techniques such as high-resolution imaging, infrared scanning, and geospatial analysis enhance its accuracy and usefulness. While IMINT provides valuable context, its effectiveness often depends on timely collection and expert interpretation.

E. Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT)

Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT) is a highly technical form of intelligence that focuses on detecting, tracking, and analyzing distinctive signatures produced by specific activities or phenomena. These can include radar waves, thermal emissions, acoustic vibrations, seismic events, or nuclear byproducts. MASINT is often used in arms control verification, counter-proliferation, and battlefield monitoring. Its strength lies in its ability to detect what is not visible to the naked eye, offering unique insights that complement other collection methods.

F. Cyber Intelligence

Cyber Intelligence is centered on monitoring and analyzing activities within cyberspace, including network traffic, system vulnerabilities, malicious software, and hacker operations. It plays a vital role in identifying and countering cyber threats such as espionage, sabotage, or criminal intrusions. Cyber intelligence supports both defensive and offensive operations by assessing digital risks, protecting critical infrastructure, and attributing cyberattacks to specific actors. In the digital age, it has become a cornerstone of national security, corporate defense, and information assurance.

Considerations for Targeting and Prioritizing Collection Efforts

A. Importance of Targeting Specific Information Needs

Effective intelligence collection begins with clearly defined priorities. By establishing specific intelligence requirements, often derived from national security strategies, operational plans, or decision-maker requests, agencies can avoid collecting irrelevant or redundant data. Targeted collection enhances accuracy, timeliness, and utility of intelligence products. This prioritization also helps align limited resources with high-value objectives, ensuring that collectors are not overwhelmed with excess information or distracted by low-priority targets. Tools such as Priority Intelligence Requirements (PIRs) and Essential Elements of Information (EEIs) are often used to structure targeting and collection planning.

B. Risk Assessment and Mitigation Strategies

Risk assessment is central to ethical and secure intelligence collection. Different methods of collection, human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), or open-source intelligence (OSINT), carry varying levels of risk to personnel, sources, national reputation, and operational integrity. For instance, clandestine operations may endanger human sources, while cyber collection can expose an agency to retaliatory attacks. Mitigation strategies may include:

-

Implementing secure communication channels and encryption to protect sensitive data.

-

Using cover identities, anonymization, or proxy networks to safeguard collectors and sources.

-

Establishing contingency protocols in case of exposure or compromise.

-

Applying legal and ethical guidelines to minimize political or reputational fallout.

Proactive risk management ensures the long-term sustainability and credibility of intelligence operations.

C. Balancing Proactive and Reactive Collection Efforts

An optimal intelligence posture requires balancing proactive and reactive collection approaches:

-

Proactive Collection: Anticipatory efforts guided by intelligence priorities, long-term threat assessments, and strategic forecasting. For example, monitoring cyber threat actors before they launch attacks.

-

Reactive Collection: Rapid response to emerging events such as terrorist incidents, military conflicts, or natural disasters. This ensures intelligence remains relevant in fast-moving environments.

Balancing these approaches allows agencies to maintain strategic foresight while remaining operationally agile, preventing intelligence blind spots and ensuring timely support to policymakers.

D. Continuous Evaluation and Adjustment

Targeting and prioritization are not static. Intelligence requirements evolve as threats, technologies, and political contexts change. Regular review of collection priorities, coupled with feedback from end-users (e.g., policymakers, military commanders), ensures collection remains aligned with real-world needs. Leveraging data-driven assessments and lessons learned from past operations helps refine targeting strategies and improve efficiency over time.

Read Also: Role of Intelligence in National Security and Military Operations

Coordination and Collaboration in Intelligence Collection

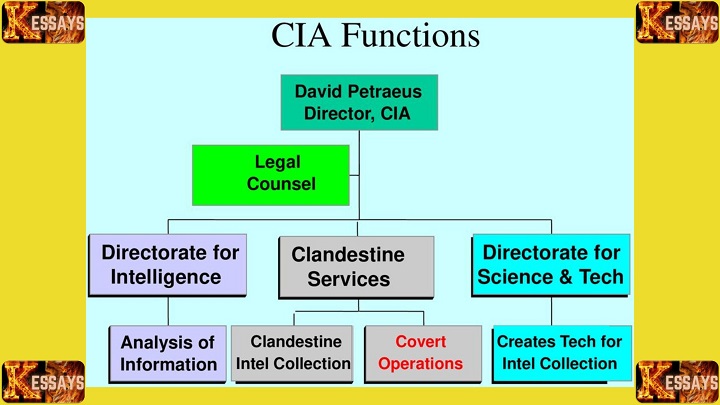

A. Interagency Cooperation and Information Sharing

Effective intelligence collection requires seamless cooperation among diverse government agencies, military units, and security organizations. Information sharing helps prevent intelligence gaps, reduces duplication of effort, and ensures resources are used efficiently. Interagency task forces and joint operations centers are increasingly used to pool expertise and synchronize activities. However, cooperation must also address challenges such as differing mandates, organizational cultures, and classification barriers that can hinder smooth collaboration. Developing standardized communication protocols, joint training programs, and shared databases helps mitigate these obstacles.

B. Liaison with External Stakeholders and Partners

Beyond interagency collaboration, intelligence collection often depends on strong relationships with external partners. These may include foreign intelligence services, international organizations, law enforcement agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academic researchers, and private sector entities such as technology firms or cybersecurity companies. Such partnerships provide access to unique datasets, technological expertise, or on-the-ground perspectives that government agencies alone may lack. Building mutual trust, establishing clear legal frameworks, and respecting the sovereignty of partners are critical to maintaining effective and ethical collaboration.

C. Role of Intelligence Fusion Centers

Intelligence fusion centers act as central nodes for coordinating and integrating intelligence efforts across multiple domains. By bringing together representatives from federal, state, and local agencies, as well as sometimes private sector partners, fusion centers consolidate diverse streams of data into actionable intelligence. These centers enhance situational awareness, support crisis management, and enable quicker responses to emerging threats. Modern fusion centers also increasingly employ advanced technologies such as big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and geospatial mapping to detect hidden patterns and generate predictive insights.

D. Overcoming Barriers to Collaboration

Despite the benefits of coordination, barriers such as information silos, bureaucratic rivalry, security classification restrictions, and concerns over misuse of shared data can limit collaboration. Overcoming these requires building a culture of trust, implementing need-to-share policies (balanced with need-to-know protections), and establishing clear oversight mechanisms. Joint training exercises, cross-agency secondments, and shared technological platforms can further strengthen collaborative practices.

Analysis and Evaluation of Collected Intelligence

A. Quality Control and Validation of Information

The first stage in analyzing collected intelligence is ensuring its quality and reliability. Raw data is often incomplete, contradictory, or even deliberately deceptive, which makes rigorous validation essential. Quality control involves assessing accuracy, timeliness, and relevance while discarding unreliable or redundant material. Validation can be achieved by cross-checking information against independent sources, corroborating details through multiple collection methods, and subjecting data to critical scrutiny. A robust validation process not only strengthens credibility but also protects decision-makers from acting on flawed or manipulated intelligence.

B. Data Processing and Exploitation

Once validated, information must be organized into a usable form. Data processing and exploitation involve categorizing, structuring, and formatting raw material to highlight its significance. Modern intelligence work increasingly relies on advanced tools such as machine learning, big data analytics, and data visualization platforms to identify patterns, anomalies, and hidden linkages within vast datasets. Data fusion; combining inputs from different disciplines such as HUMINT, SIGINT, and IMINT, which creates a richer, multidimensional intelligence picture. Effective exploitation transforms raw data into knowledge that can directly inform strategic, operational, or tactical decisions.

C. Analytical Techniques and Tools

Analysis requires both human expertise and technical tools. Analysts employ methods such as link analysis to reveal relationships between people or organizations, geospatial analysis to map activity across terrain, and predictive modeling to anticipate future developments. Pattern recognition, sentiment analysis, and network analysis also play a growing role in identifying emerging threats or opportunities. While these tools enhance analytical rigor, human judgment remains central in interpreting context, weighing uncertainty, and distinguishing between correlation and causation. A well-trained analyst ensures that technology supports rather than replaces critical thinking.

D. Producing Actionable Intelligence Products

The ultimate goal of the analytical process is to generate actionable intelligence that supports effective decision-making. Intelligence products, ranging from situation reports and threat assessments to forecasts and policy briefs, must be clear, concise, and tailored to the needs of the end user. They should highlight not only what is known but also what is unknown, outlining levels of confidence and potential gaps. Recommendations should be realistic, timely, and linked directly to the original intelligence requirements. Actionable intelligence provides decision-makers with both situational awareness and practical options for response.

E. Addressing Uncertainty and Bias in Analysis

All intelligence carries a degree of uncertainty, and acknowledging this is critical for credibility. Analysts must avoid overstating confidence levels and instead communicate the likelihood or probability of outcomes. Structured analytic techniques, such as red teaming, devil’s advocacy, or scenario planning, can help minimize cognitive bias and challenge assumptions. Peer review and collaborative analysis further strengthen objectivity, ensuring that conclusions are evidence-based rather than shaped by institutional or personal bias.

F. Feedback and Continuous Improvement

Finally, analysis should not be seen as a one-way process. Continuous feedback from decision-makers allows analysts to refine their products, adjust focus, and prioritize the most relevant intelligence requirements. Post-action reviews and after-action assessments also help identify which analyses were most accurate or useful, feeding into an ongoing cycle of improvement. This feedback loop enhances not only the quality of analysis but also the adaptability of the entire intelligence process.

Read Also: The Role of Government Policies in Perpetuating the Eviction Crisis

Challenges and Ethical Considerations in Intelligence Collection

A. Legal and Privacy Implications

Intelligence collection must operate within the boundaries of national and international legal frameworks. Different jurisdictions impose restrictions on the type of information that can be collected, the methods employed, and the extent of surveillance activities. Privacy protections are particularly critical, as unchecked collection efforts can easily infringe upon civil liberties and human rights. Oversight mechanisms, such as legislative committees or independent watchdogs, are often established to ensure accountability and legality. Failure to comply with these frameworks not only exposes organizations to legal repercussions but also undermines public trust, which is vital for sustaining intelligence operations in democratic societies.

B. Protecting Sources and Methods

The confidentiality of sources and the security of collection methods are fundamental to operational integrity. Human sources, such as informants, defectors, or covert agents, face significant risks if their identities are revealed, ranging from reputational harm to physical danger. Similarly, exposing technical methods or surveillance technologies may allow adversaries to evade detection, neutralize collection capabilities, or exploit vulnerabilities. Organizations must therefore implement stringent counterintelligence measures, encryption protocols, and compartmentalization practices to safeguard sensitive information. Protecting sources and methods is not only a matter of security but also of maintaining credibility and long-term effectiveness.

C. Maintaining Objectivity and Avoiding Bias

Intelligence collection is vulnerable to distortions arising from personal biases, organizational culture, or political pressure. Collectors and analysts may unconsciously prioritize certain sources, overvalue specific types of information, or filter findings to align with preconceived expectations. Such biases can compromise the accuracy and reliability of intelligence products, leading to flawed assessments and poor decision-making. To mitigate this risk, organizations must promote rigorous methodological standards, encourage peer review, and foster a culture of critical thinking. Ensuring diversity of sources and perspectives also helps counterbalance individual or institutional bias.

D. Technological Risks and Ethical Boundaries

The rapid advancement of surveillance technologies, artificial intelligence, and cyber tools presents both opportunities and ethical dilemmas. While these technologies expand collection capabilities, they also raise questions about proportionality, transparency, and unintended consequences. For instance, mass data harvesting may yield valuable intelligence but risks sweeping up vast amounts of irrelevant personal data, violating the principle of minimal intrusion. Similarly, offensive cyber operations can cross into legally ambiguous or morally questionable territory. Balancing technological advantage with ethical restraint is therefore an ongoing challenge.

E. Accountability and Oversight

Intelligence agencies must balance secrecy with accountability. Excessive secrecy can erode democratic oversight and create conditions for abuse of power, whereas excessive transparency may jeopardize operations. Mechanisms such as judicial review, legislative oversight, and internal compliance units help strike this balance. Ethical intelligence collection requires clear policies, well-defined limits, and accountability structures that protect both national security interests and individual rights.

Read Also: Non-Plagiarized Essay Help

Adjusting and Adapting the Intelligence Collection Plan

A. Continuous Evaluation and Feedback

An intelligence collection plan is not a static framework; it requires ongoing evaluation to remain effective. Regular assessments help determine whether the plan is meeting established intelligence requirements, responding adequately to operational needs, and producing actionable insights. Feedback loops involving collectors, analysts, and decision-makers are essential, as they highlight gaps, inefficiencies, and opportunities for refinement. This continuous process ensures that the plan evolves alongside the realities of the operating environment.

B. Incorporating Lessons Learned and Best Practices

The integration of lessons learned and best practices is a critical step in strengthening future collection efforts. By systematically analyzing both successes and failures, organizations can identify what strategies were effective, what challenges hindered outcomes, and how methods can be improved. Knowledge-sharing across teams and departments helps institutionalize these lessons, preventing repeated mistakes and fostering innovation. This practice not only enhances efficiency but also builds a stronger foundation for long-term intelligence capability.

C. Flexibility in Response to Changing Threats and Priorities

Perhaps the most vital characteristic of an intelligence collection plan is its adaptability. Threat landscapes and operational priorities are inherently dynamic, requiring the plan to be flexible and responsive. This may involve shifting resources to address urgent intelligence gaps, adopting new technologies, or revising methods to counter emerging challenges. A rigid plan quickly loses relevance, but a flexible one enables decision-makers to stay ahead of adversaries and maintain a proactive stance in uncertain environments.

Comments are closed!