Introduction to Clinical Microscopy

Microscopy is often the first window into the invisible world of disease-causing microbes, allowing scientists and clinicians to detect and study bacteria that cannot be seen with the naked eye. How microscopy helps identify bacteria in clinical samples is central to modern microbiology because early and accurate identification of microorganisms can mean the difference between effective treatment and serious complications. In clinical settings, the microscopic examination of bacteria provides immediate visual clues about the presence of infection, guiding further testing and medical decisions.

The importance of microscopy in microbiology lies in its ability to reveal the basic characteristics of microorganisms, such as shape, size, and arrangement. These observations help narrow down possible bacterial groups and distinguish harmless microbes from pathogens. Because many infectious diseases progress rapidly, identifying disease-causing microbes as early as possible is essential for patient care and infection control.

Microscopic examination plays a critical role in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. While microscopy alone does not always provide a definitive diagnosis, it serves as a foundational microscopic test for disease, directing the use of stains, cultures, and other diagnostic methods. By combining different types of microscope with targeted laboratory techniques, clinicians can determine whether microscopy can diagnose bacteria in clinical samples directly or whether additional testing is required.

Purpose of Using a Microscope in a Clinical Laboratory

What is the main purpose of using a microscope in microbiology

The main purpose of using a microscope in microbiology is to make invisible microorganisms visible so they can be studied and identified. Many disease-causing microbes are far too small to be seen with the naked eye, yet they play a major role in human health and disease. Through microscopic examination, microbiologists can observe bacterial size, shape, and arrangement, which provides the first clues about the identity of an organism. This foundational step supports the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases by guiding which stains, cultures, or molecular tests should be performed next.

Why a microscope is used to observe bacteria in clinical samples

A microscope is used to observe bacteria in clinical samples because it allows rapid assessment of whether microorganisms are present at the site of infection. The microscopic examination of bacteria from blood, wound swabs, or body fluids can reveal patterns that suggest specific bacterial groups. In many cases, microscopy helps narrow down possibilities long before culture results are available. This early information is especially valuable when dealing with fast-spreading or severe infections, where treatment decisions must be made quickly.

How microscopy helps doctors detect disease at an early stage

Microscopic Examination of Bacteria

What microscopic examination of bacteria involves

Microscopic examination of bacteria is a systematic process used to visualize microorganisms that cannot be seen with the naked eye. In clinical microbiology, this examination serves as an early microscopic test for disease and is a critical step in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. Using appropriate types of microscope, such as brightfield or darkfield microscopes, laboratory professionals observe bacterial cells directly from clinical samples. The goal is not always to make a final diagnosis, but to rapidly determine whether disease-causing microbes are present and to gather initial information that guides further testing, such as staining, culturing, or molecular analysis.

How bacteria are prepared and viewed in clinical samples

Sample collection

The procedure begins with the careful collection of a clinical sample from the patient. Common sources include wound swabs, blood, urine, sputum, or other bodily fluids. Proper collection is essential to avoid contamination and to ensure that the bacteria observed truly represent the cause of infection.

Slide preparation

A small portion of the specimen is placed onto a clean glass slide. If the sample is thick, it is spread into a thin smear to allow light to pass through easily. Thin smears improve clarity and ensure that individual bacterial cells can be observed.

Air drying and fixation

After the smear is prepared, it is allowed to air dry. Fixation then follows, usually by gently heating the slide or using a chemical fixative. Fixation attaches the bacteria to the slide, kills the organisms, and preserves their structure so they do not wash away during staining.

Staining the specimen

Staining is used to increase contrast because bacteria are naturally transparent. Common methods include the Gram stain, which differentiates bacteria into gram-positive and gram-negative groups based on cell wall structure. Stains bind to cellular components, making bacterial cells visible against the background.

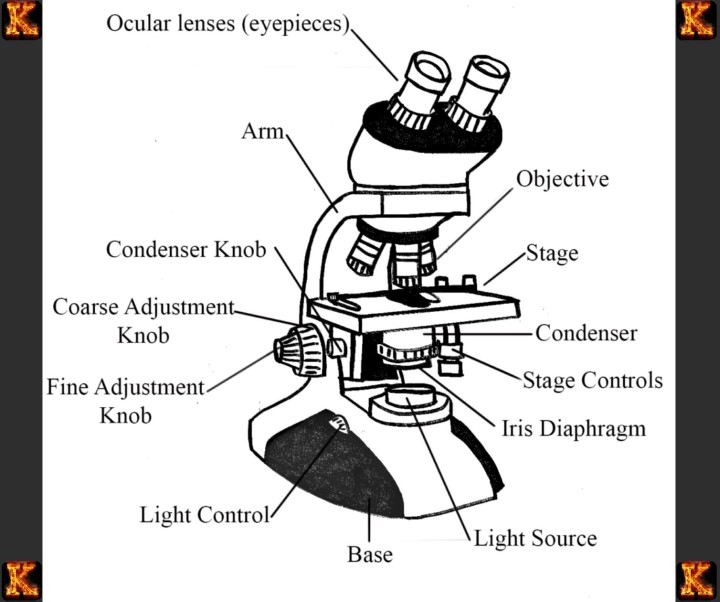

Microscopic viewing

Once stained, the slide is placed on the microscope stage. The specimen is first examined under low magnification to locate the cells, then under higher magnification, often using oil immersion, to observe fine details. This step allows the examiner to assess bacterial shape, arrangement, and staining characteristics.

Interpretation of observations

Finally, the observed features are interpreted in a clinical context. These findings help guide further laboratory testing and support early decision-making in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases.

What information microscopic examination reveals about disease-causing microbes

Cell shape and size

Microscopy allows clinicians to determine the basic shape and size of disease-causing microbes. Bacteria may appear as cocci, which are spherical, bacilli, which are rod-shaped, or spiral forms. Size differences can also be observed, helping distinguish bacteria from other cells such as white blood cells or debris. These basic observations immediately narrow down the possible groups of bacteria involved in an infection.

Cell arrangement and growth patterns

The way bacteria are arranged provides additional clues. Some bacteria appear in chains, others in pairs, and some form clusters resembling grapes. For example, grape-like clusters suggest staphylococcal species, while chains are typical of streptococci. Recognizing these patterns helps clinicians rapidly associate the infection with specific bacterial groups.

Staining characteristics

Staining techniques, especially the Gram stain, reveal important differences in bacterial cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria retain the purple stain, while gram-negative bacteria appear pink after counterstaining. This distinction is clinically significant because it influences antibiotic selection and treatment strategies.

Evidence of infection and inflammation

Microscopy can also show bacteria in relation to pus or white blood cells. The presence of numerous bacteria alongside immune cells indicates an active infection. This visual evidence supports clinical suspicion and confirms that the microorganisms observed are likely responsible for the disease.

Guidance for further diagnosis

Although microscopy does not always identify the exact species, it provides rapid and valuable information. These observations guide additional tests, such as culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing, supporting timely treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

How Microscopy Diagnoses Bacteria in Clinical Samples

Does microscopy diagnose bacteria in clinical samples directly

Microscopy plays a critical role in the early evaluation of clinical samples, but it does not usually provide a complete or definitive diagnosis on its own. By examining specimens under the microscope, clinicians can rapidly confirm the presence of bacteria and assess key features such as shape, arrangement, and staining behavior. These observations allow healthcare professionals to classify bacteria into broad groups, such as gram-positive cocci or gram-negative bacilli. In urgent clinical situations, this preliminary information is valuable because it helps guide immediate treatment decisions while more specific tests are pending.

How microscopy contributes to the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases

Rapid Detection of Disease-Causing Microbes

Microscopy is often the first microscopic test for disease performed in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. By directly visualizing bacteria, fungi, or protozoa in clinical samples such as wound exudates, blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid, clinicians obtain immediate visual confirmation of the presence of disease-causing microbes. For instance, observing spherical, grape-like clusters in a wound sample under a brightfield microscope can suggest a staphylococcal infection, whereas chains of cocci may indicate streptococci. This early detection allows rapid initiation of supportive care and empiric therapy while awaiting culture or molecular confirmation.

Guiding Further Diagnostic Testing

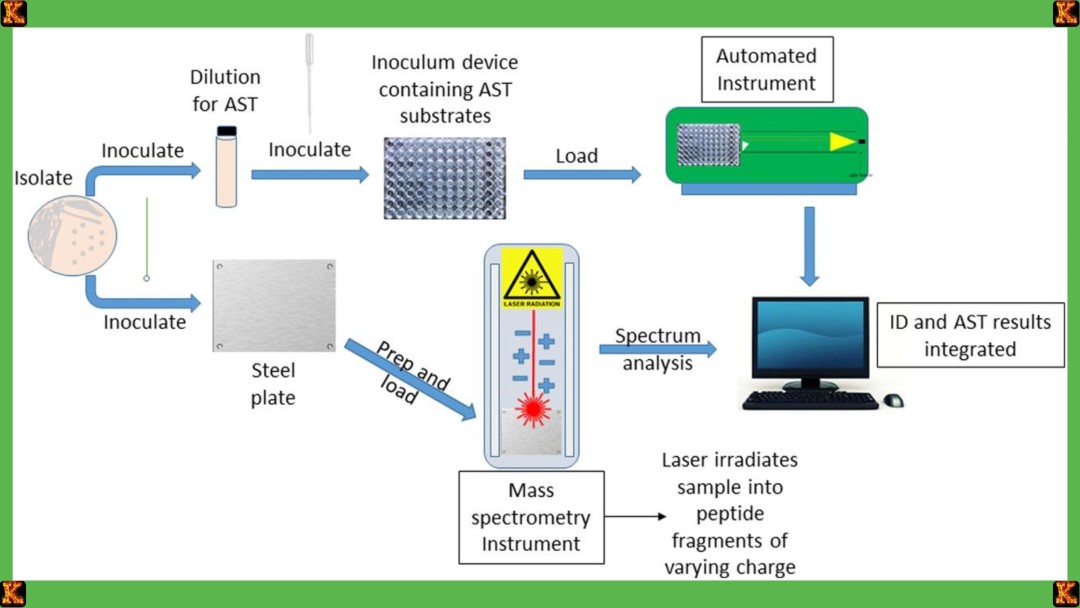

Microscopy informs the selection of subsequent laboratory tests. After a Gram stain, for example, the observed cell wall characteristics, whether gram-positive or gram-negative, directly influence which culture media, selective enrichment protocols, or biochemical assays should be used. In cases where rapid identification is critical, such as suspected meningitis, fluorescent antibody microscopy can help identify pathogens like Neisseria meningitidis within hours. Similarly, the identification of acid-fast bacilli in sputum by Ziehl-Neelsen staining provides immediate guidance for tuberculosis testing, illustrating how microscopic examination supports the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Enhancing Diagnostic Efficiency

By narrowing the potential range of pathogens, microscopy reduces the time and resources needed for definitive identification. It allows laboratories to focus molecular diagnostics or antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the most likely organisms, optimizing workflow and improving clinical outcomes. This approach is especially critical in high-volume or resource-limited settings, where rapid decision-making is essential for controlling the spread of infection. In sum, microscopy provides both visual evidence and strategic direction, forming the cornerstone of laboratory diagnosis in clinical microbiology.

Limitations of microscopy and the need for additional tests

Resolution and Sensitivity Constraints

Although microscopy is indispensable for the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases, it has inherent limitations. Some bacteria, such as Mycoplasma species, are too small to be reliably visualized with standard light microscopy. Similarly, pathogens present in low numbers may evade detection, leading to false negatives. Even with staining techniques such as Gram, acid-fast, or fluorescent dyes, microscopic examination cannot always distinguish closely related species, which can share similar morphologies but differ significantly in pathogenicity or antibiotic susceptibility.

Lack of Functional and Resistance Information

Microscopy cannot determine whether observed bacteria are alive, nor can it provide information about antimicrobial resistance. For example, while Gram-positive cocci may be identified as Staphylococcus species, microscopy alone cannot distinguish methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from methicillin-sensitive strains. This limitation necessitates additional culture-based testing or molecular assays to determine the correct treatment, emphasizing that microscopy serves as an initial screening rather than a definitive diagnostic method.

Integration with Complementary Tests

To overcome these limitations, microscopy is integrated with culture techniques, biochemical assays, and molecular diagnostics such as PCR or antigen detection. For instance, Gram-stained sputum samples may reveal gram-negative rods suggestive of Klebsiella species, but culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing are required to confirm the identity and guide therapy. Similarly, microscopic detection of fungal hyphae in a tissue biopsy can prompt fungal culture or DNA-based identification for definitive diagnosis.

Clinical Implications

Recognizing the strengths and limitations of microscopic examination ensures that clinicians can interpret results within context. While microscopy provides rapid, preliminary insight into the presence and morphology of disease-causing microbes, it must be coupled with additional tests for accurate laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. This integrated approach enhances patient outcomes, supports effective antimicrobial stewardship, and prevents the misdiagnosis or under-treatment of serious infections.

Read Also: Risk Prediction Models in Clinical Practice

Identifying Bacteria Under a Microscope

How do you identify bacteria under a microscope

Step 1: Collection and Preparation of Clinical Samples

The first step in identifying bacteria under a microscope is obtaining an appropriate clinical sample. The type of sample depends on the suspected site of infection and the suspected pathogen. For respiratory infections, sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may be collected. For urinary tract infections, midstream urine is preferred. Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or wound swabs are used for systemic or localized infections. Proper collection ensures that disease-causing microbes are present in sufficient quantity for microscopic examination.

Once collected, the sample is typically smeared onto a clean glass slide and fixed by heat or chemicals to preserve bacterial morphology. This preparation step is essential for accurate visualization and prevents distortion of the bacteria, which could lead to misidentification. For example, improper fixation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum may reduce the visibility of acid-fast bacilli during Ziehl-Neelsen staining.

Step 2: Selection of Microscopic Test

After sample preparation, the microbiologist chooses an appropriate microscopic test for disease based on the suspected bacteria. The Gram stain remains the most commonly used test. It separates bacteria into gram-positive or gram-negative categories according to their cell wall composition. Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, retain the crystal violet stain and appear purple, while gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae, take up the counterstain and appear pink. In infections requiring urgent identification, fluorescent antibody microscopy may be used.

This technique employs antibodies tagged with fluorescent dyes that bind specifically to bacterial antigens, enabling rapid detection of pathogens like Neisseria meningitidis in cerebrospinal fluid. Acid-fast staining is chosen when tuberculosis or other mycobacterial infections are suspected, as Mycobacterium species resist decolorization with acid-alcohol due to their high lipid content.

Step 3: Visualization and Microscopic Examination

Once the staining method is applied, the slide is examined under the microscope using the appropriate type of microscope. Bright-field microscopes are commonly used for Gram and acid-fast stains, whereas fluorescence microscopes are necessary for antibody-based detection. During microscopic examination, the microbiologist observes bacterial shape, size, arrangement, and staining characteristics. Cocci may be seen in clusters, chains, or pairs, while rods vary in length and thickness. Spiral or curved bacteria may indicate pathogens such as Campylobacter or Vibrio species. Microscopic examination allows rapid, preliminary identification of the bacterial species in the clinical sample, providing essential information before culture or molecular confirmation.

Step 4: Interpretation and Preliminary Identification

After visualization, the observed bacterial features are interpreted in the context of clinical information. Gram-positive cocci in clusters suggest Staphylococcus species, while gram-positive cocci in chains suggest Streptococcus species. Gram-negative rods in urine or sputum may indicate E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae. Acid-fast bacilli in sputum are indicative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, whereas fluorescently labeled diplococci in cerebrospinal fluid confirm Neisseria meningitidis.

These observations enable the microbiologist to make a preliminary diagnosis and recommend appropriate culture media, selective enrichment protocols, or molecular tests for confirmation. Microscopy thus serves both as a diagnostic tool and as a guide for subsequent laboratory investigations, ensuring timely and accurate laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Step 5: Integration with Confirmatory Tests

The final step involves integrating microscopic findings with additional laboratory tests. While microscopy diagnose bacteria in clinical samples rapidly, confirmatory tests such as bacterial culture, biochemical assays, or polymerase chain reaction are required for definitive identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing. For instance, gram-negative rods observed in sputum may be further cultured on MacConkey agar to differentiate E. coli from Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Similarly, acid-fast bacilli detected in sputum are cultured on Lowenstein-Jensen medium to confirm Mycobacterium tuberculosis and to perform drug susceptibility testing. By combining microscopic examination with these confirmatory techniques, laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases is both rapid and accurate, providing a solid foundation for effective patient management.

Role of cell shape, size, and arrangement in identification

Shape, Size, and Arrangement of Bacteria

Bacterial morphology is a primary feature observed during microscopic examination and is essential for laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. The shape of bacteria, including cocci, bacilli, spirilla, or vibrios, provides immediate clues about the likely genus. Cocci may appear singly, in pairs, chains, or clusters, while bacilli vary from short rods to filamentous forms. For example, Staphylococcus aureus forms spherical cocci in clusters, whereas Streptococcus pyogenes forms chains. Spirilla such as Campylobacter and curved rods like Vibrio cholerae can also be distinguished under a microscope. Observing these features allows microscopy to diagnose bacteria in clinical samples rapidly and guides further laboratory testing.

Diagnostic Role of Cell Size

The size of bacterial cells is a critical factor in microscopic identification. Slender rods, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, differ visibly from broad bacilli like Corynebacterium species, and small cocci like Neisseria meningitidis require higher magnification for accurate visualization. Size also affects staining properties and the appearance of cellular arrangements. Measuring cell dimensions under bright-field or phase-contrast microscopy enhances the specificity of preliminary identification. This enables microbiologists to distinguish between pathogens with similar shapes but different clinical significance, helping prioritize confirmatory culture, biochemical assays, or molecular testing in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Arrangement Patterns and Identification

The spatial arrangement of bacterial cells provides additional diagnostic clues during microscopic examination. Cocci may be arranged singly, in pairs, chains, or clusters. Streptococcus species typically form chains, whereas Staphylococcus species form irregular clusters. Bacilli may appear singly, in pairs, or in palisades, as observed with Corynebacterium diphtheriae. These patterns are highlighted during Gram staining, acid-fast staining, or phase-contrast microscopy. Recognizing bacterial arrangements in clinical samples allows microbiologists to make accurate preliminary assessments of disease-causing microbes, guiding the choice of selective culture media and other laboratory tests, ultimately supporting rapid and reliable laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Importance of microscopy in distinguishing different microorganisms

Rapid Preliminary Identification

Microscopy allows for the rapid preliminary identification of microorganisms in clinical samples. By observing size, shape, and staining properties, laboratory personnel can quickly narrow down the possible pathogens. For example, gram-negative diplococci in cerebrospinal fluid suggest Neisseria meningitidis, while gram-positive diplococci indicate Streptococcus pneumoniae. This early identification is crucial for initiating timely empiric therapy before confirmatory culture or molecular tests are completed, especially in life-threatening infections such as meningitis or sepsis. Rapid microscopic examination therefore provides a first line of diagnostic insight in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.Differentiation Between Microorganism Types

Microscopy helps distinguish bacteria from fungi, protozoa, and other microorganisms in clinical specimens. Intracellular bacteria, such as Rickettsia, can be seen in blood smears, while fungi like Candida appear as budding yeast forms. Protozoa such as Plasmodium species are visible within red blood cells. This differentiation ensures that disease-causing microbes are correctly identified and prevents misdiagnosis. By separating organisms based on morphology and staining characteristics, microscopy diagnose bacteria in clinical samples while also highlighting non-bacterial pathogens that require different laboratory approaches or treatment strategies.Guidance for Culture and Laboratory Tests

Microscopic examination informs the selection of culture media and enrichment techniques specific to the suspected pathogen. Observing bacteria in clinical samples allows microbiologists to choose selective or differential media, reducing the time and resources required for culture. For example, the detection of gram-negative rods in urine can guide the use of MacConkey agar to differentiate Escherichia coli from Klebsiella pneumoniae. By linking microscopic observations to targeted laboratory tests, microscopy enhances the efficiency and accuracy of the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.Monitoring Disease Progression

Microscopy is essential for monitoring the course of infections and evaluating treatment effectiveness. Repeated microscopic examination of clinical samples can show changes in bacterial load, the presence of intracellular pathogens, or the persistence of fungal cells. This is particularly valuable in chronic infections such as tuberculosis, where Ziehl-Neelsen staining can track Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum samples over time. Continuous microscopic evaluation provides clinicians with timely feedback to adjust therapies, ensuring more effective management of infectious diseases.

Types of Microscope Used in Clinical Microbiology

Overview of Types of Microscopes Used in Laboratories

Microscopes are fundamental tools in clinical microbiology for the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. Different types of microscopes provide varying levels of resolution, contrast, and specificity, allowing microbiologists to observe bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other microorganisms in clinical samples. The selection of a microscope depends on the type of organism, the staining method used, and the diagnostic requirement. By understanding the capabilities of each microscope, laboratory personnel can choose the most appropriate method to diagnose bacteria in clinical samples efficiently, ensuring accurate and timely laboratory results.

Brightfield Microscopy and Its Role in Bacterial Diagnosis

Brightfield microscopy is the most commonly used microscope in clinical laboratories. It relies on simple light transmission through stained specimens to visualize bacterial morphology, arrangement, and staining characteristics. Techniques such as Gram staining, Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining, and simple staining are performed using brightfield microscopes to rapidly identify disease-causing microbes. For example, gram-positive cocci in clusters observed under a brightfield microscope can suggest Staphylococcus aureus, while gram-negative rods may indicate Escherichia coli. Brightfield microscopy is widely used because it is cost-effective, easy to operate, and sufficient for most routine laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Darkfield and Phase-Contrast Microscopy in Microscopic Examination

Darkfield and phase-contrast microscopy enhance the visualization of bacteria that are difficult to see using brightfield microscopy. Darkfield microscopy increases contrast by illuminating specimens against a dark background, making thin or motile bacteria such as Treponema pallidum visible. Phase-contrast microscopy improves the observation of unstained live cells by converting differences in refractive index into contrast. These techniques allow microscopic examination of delicate or fastidious organisms, providing additional diagnostic information. They are particularly useful for specialized cases where conventional brightfield microscopy may fail to identify disease-causing microbes accurately.

Limitations of Advanced Microscopes in Routine Diagnosis

High Cost

Advanced microscopes, such as fluorescence and electron microscopes, are expensive to purchase and maintain. The initial investment for these instruments is significant, and routine maintenance requires specialized technical support. High cost limits their availability to large or well-funded laboratories, making them impractical for many clinical settings. As a result, most routine bacterial diagnosis relies on more affordable microscopes like brightfield or phase-contrast, which provide sufficient resolution for preliminary identification of disease-causing microbes in clinical samples.

Technical Complexity

Using advanced microscopes requires specialized training and expertise. Fluorescence microscopy involves precise handling of fluorescent dyes and careful control of illumination, while electron microscopy requires preparation of ultra-thin specimens and operation under vacuum conditions. The technical complexity increases the risk of errors during sample preparation or imaging. Many routine clinical laboratories lack personnel with this level of expertise, which restricts the routine use of these microscopes despite their high resolution and diagnostic capabilities.

Longer Preparation Times

Preparation of samples for advanced microscopy is often time-consuming. Electron microscopy requires fixation, dehydration, embedding, and sectioning of specimens, while fluorescence microscopy may involve antibody labeling and incubation steps. These extended preparation times delay the availability of results. In urgent cases, such as suspected bacterial meningitis or sepsis, rapid preliminary diagnosis is critical, making brightfield or phase-contrast microscopy more practical for routine laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Limited Accessibility

Advanced microscopes are not universally available in all clinical laboratories. Resource-limited settings may lack both the instruments and the supporting infrastructure, such as stable electricity and climate-controlled rooms. This limited accessibility means that advanced microscopy cannot be relied upon for routine diagnosis in many healthcare facilities. Microscopic examination using simpler, widely available microscopes remains the mainstay for rapid identification of bacteria and other disease-causing microbes in clinical samples.

Read Also: Swift River Virtual Clinicals Answers

Microscopy and the Laboratory Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

Role of Microscopy in the Laboratory Diagnosis Process

Microscopy serves as a foundational step in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases. It allows the direct observation of disease-causing microbes in clinical samples, providing rapid preliminary information that guides subsequent testing. By examining bacterial morphology, arrangement, and staining characteristics, microbiologists can identify potential pathogens before performing culture or molecular assays. For example, observing gram-positive cocci in clusters in a blood smear may suggest Staphylococcus aureus, while gram-negative rods in urine indicate Escherichia coli. This early insight streamlines the laboratory workflow and informs clinical decision-making.

Microscopic Tests as a Critical First Step

Microscopic tests for disease are essential because they provide immediate diagnostic clues that cannot be obtained from culture alone. Techniques such as Gram staining, Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining, and fluorescent antibody microscopy allow microbiologists to detect and differentiate bacteria, fungi, and protozoa directly in patient specimens. Rapid detection of pathogens like Neisseria meningitidis in cerebrospinal fluid or Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum can guide urgent clinical interventions. Microscopy diagnose bacteria in clinical samples efficiently, reducing delays in therapy and improving patient outcomes while serving as the first step in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Integration with Staining and Culture Methods

Microscopy works synergistically with staining and culture methods to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Stains highlight specific bacterial features, while microscopy allows direct visualization, confirming the presence of disease-causing microbes. Observations from microscopic examination inform the choice of selective or differential culture media, enrichment protocols, and biochemical or molecular tests. For instance, gram-negative rods observed in urine may be cultured on MacConkey agar to differentiate Escherichia coli from Klebsiella species. This integrated approach ensures that the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases is both rapid and reliable, providing a complete framework for pathogen identification and patient management.

Conclusion

Microscopy plays a central role in the laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases by enabling the direct visualization of disease-causing microbes in clinical samples. Through microscopic examination, microbiologists can rapidly assess bacterial shape, size, arrangement, and staining characteristics, distinguishing gram-positive from gram-negative organisms, identifying acid-fast bacilli, and detecting other pathogens such as fungi or protozoa. This preliminary identification guides the selection of appropriate culture media, enrichment protocols, and confirmatory molecular tests, allowing timely and accurate laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Beyond its diagnostic value, microscopic examination remains a critical educational tool in microbiology, training students and laboratory personnel to recognize bacterial morphology and understand microbial physiology. Mastery of microscopy provides foundational skills essential for both research and clinical practice, ensuring that laboratory personnel can identify bacteria in clinical samples effectively, contribute to patient care, and respond to emerging infectious threats with precision and confidence.