Introduction

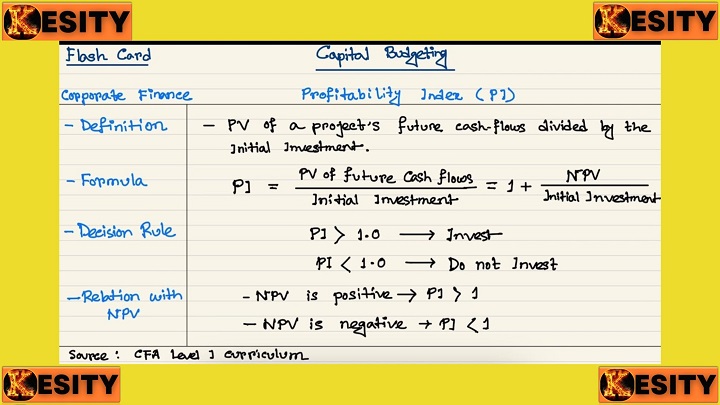

In investment appraisal, organizations often need reliable tools to decide whether a project is worth pursuing. One such tool is the profitability index (PI), which evaluates the relationship between the benefits a project is expected to generate and the costs required to undertake it. The index is calculated by dividing the present value of future cash inflows by the present value of cash outflows. In simple terms, it shows how much value a project is expected to create for every unit of currency invested.

A PI greater than one signals that the project is likely to add value, since the inflows exceed the outflows, while a PI less than one suggests that the costs are higher than the expected returns. This makes it an attractive metric for quick comparisons, especially when organizations face limited capital and must prioritize between multiple investment options.

However, while the profitability index is useful for screening projects, it is not without flaws. It does not always provide a complete picture of a project’s potential, and overreliance on it can lead to biased or misleading investment choices. Understanding its disadvantages is therefore essential for students, investors, and managers who want to apply this tool effectively within broader decision-making frameworks.

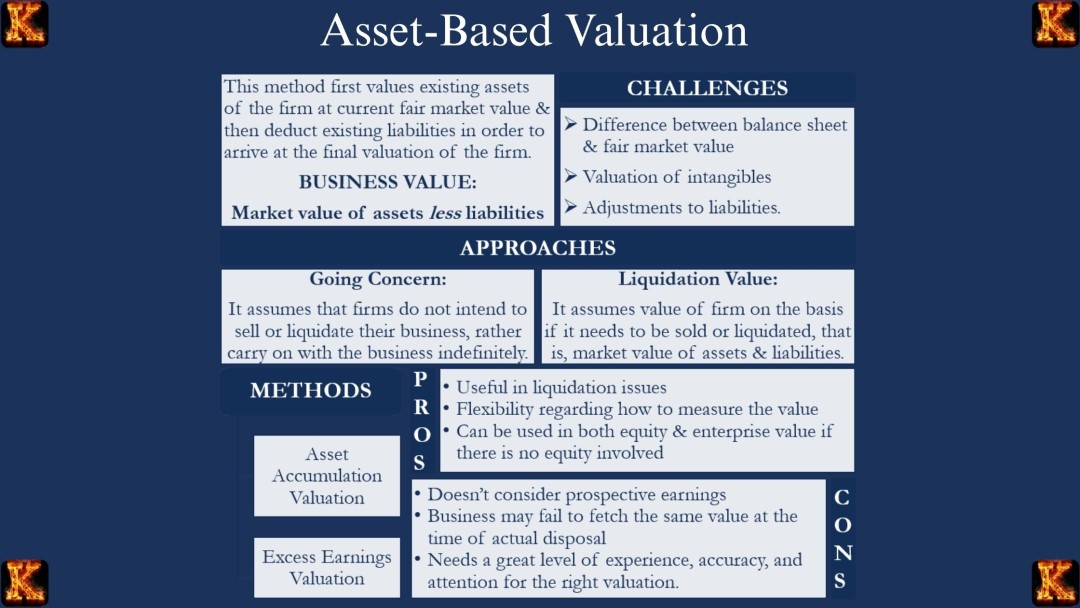

The Concept of Profitability Index

The profitability index (PI), also called the profit investment ratio or value investment ratio, is a financial tool used in capital budgeting to measure the relative profitability of an investment. It helps managers determine whether a project will generate value compared to its cost by showing the ratio between expected returns and the investment required.

The formula is expressed as:

PI = Present Value of Cash Inflows ÷ Present Value of Cash Outflows

-

Present Value of Cash Inflows refers to the value today of all future cash receipts the project is expected to generate.

-

Present Value of Cash Outflows represents the initial investment and any other costs needed to undertake the project.

Interpreting the results:

-

A PI greater than 1 means the project is expected to generate more value than it costs, indicating profitability.

-

A PI equal to 1 means the project will only break even, with benefits equal to costs.

-

A PI less than 1 means the project is not worthwhile, since costs outweigh expected returns.

The profitability index is considered useful because:

-

It provides a simple way to compare projects, especially when resources are limited.

-

It expresses profitability in relative terms, making it easy to see how much return is generated for every unit of investment.

-

It can assist in ranking multiple projects when managers need to prioritize.

However, while the calculation is straightforward, it does not capture the full complexity of investment evaluation. Projects can differ in scale, timing of returns, and strategic importance, all of which may not be reflected in a single ratio. This is why understanding its limitations is just as important as knowing how to calculate it.

Read Also: Cash in Financial Accounting: The Lifeblood of Business

Key Disadvantages of Profitability Index

The profitability index (PI) is a useful tool for evaluating the relative attractiveness of projects. However, its simplicity also limits its reliability in certain situations. For learners, it is important to understand not only how PI is calculated but also where it falls short as a decision-making tool. Below are the main disadvantages explained in detail.

1. Ignores Project Scale

The PI expresses profitability as a ratio rather than an absolute value. This can create misleading impressions when comparing projects of different sizes. For instance, a small project requiring $10,000 may produce a PI of 1.5, while a larger project requiring $1,000,000 may show a PI of 1.3. Although the smaller project has a higher ratio, the larger project generates much greater overall returns. By focusing only on relative efficiency, PI may cause managers to undervalue larger, wealth-creating opportunities.

2. Bias Toward Smaller Projects

Because of its scale limitation, PI often favors smaller projects with lower upfront costs. Organizations working under capital rationing may then allocate resources to several smaller projects that appear attractive on paper, while ignoring larger strategic investments that deliver greater long-term benefits. This bias can distort priorities, especially in industries where growth depends on large-scale projects.

3. Neglect of Cash Flow Timing

While PI accounts for the present value of inflows, it does not clearly distinguish when these cash flows occur within the project’s life. A project generating returns quickly may be more valuable in practice than one with returns concentrated far in the future, even if their PIs are similar. By overlooking the significance of timing, PI may undervalue projects that improve liquidity or support reinvestment in other ventures.

4. Dependence on Forecast Accuracy

The reliability of PI depends entirely on the accuracy of projected cash inflows and outflows. In real-world settings, forecasting is often uncertain due to market fluctuations, competitive dynamics, or changes in consumer demand. If estimates are too optimistic, the PI will overstate profitability; if too conservative, it may wrongly disqualify viable projects. This sensitivity to assumptions makes PI a potentially risky tool if used in isolation.

5. Limited Use with Mutually Exclusive Projects

When projects are mutually exclusive, meaning only one can be chosen, PI rankings can conflict with those produced by net present value (NPV). For example, one project might have a higher PI but generate less total wealth than another project with a lower PI. In such cases, relying solely on PI may result in the rejection of the project that delivers greater shareholder value.

6. Unrealistic Reinvestment Assumption

The PI implicitly assumes that interim cash inflows can be reinvested at the same rate as the index itself. In reality, reinvestment opportunities often provide lower returns, especially in volatile or saturated markets. This assumption may inflate the attractiveness of a project on paper, creating a gap between projected and actual outcomes.

7. Ignores Cost of Capital Variability

The PI calculation is based on discounting cash flows at a constant rate, which may not reflect real market conditions. In practice, interest rates, inflation, and risk profiles can shift significantly during the life of a project. By ignoring these fluctuations, PI oversimplifies the financing realities and risks associated with long-term investments.

8. Exclusion of Non-Financial Factors

Profitability index evaluations are purely financial, overlooking important qualitative factors. Strategic considerations such as environmental sustainability, compliance with regulations, or social impact are excluded. This narrow focus can cause organizations to favor financially attractive projects that may damage reputation, harm stakeholder relationships, or conflict with long-term goals.

9. Weakness in Interdependent Projects

In cases where projects are interdependent or create synergies when undertaken together, PI fails to capture the combined benefits. For example, two projects may individually appear unattractive but, when implemented jointly, may deliver strong financial and strategic returns. Evaluating them separately through PI alone could lead to their rejection and a missed opportunity for value creation.

Practical Implications of Using the Profitability Index

The disadvantages of the profitability index highlight its limited capacity as a stand-alone investment appraisal tool. While it is helpful for comparing projects quickly, relying on PI alone can distort decision-making. Below are the main implications explained in detail.

1. Biased project selection

The profitability index may favor smaller projects that have high relative returns but overlook larger projects that generate greater overall wealth. For example, a small project with a PI of 1.5 might seem more attractive than a large infrastructure project with a PI of 1.2. However, the larger project could deliver a far greater absolute net present value (NPV), meaning more real value is created for the organization even though the PI is lower.

2. Undervaluation of strategic initiatives

Projects that are strategically important may be undervalued when judged only by PI. For instance, an investment in new technology or expansion into a new market may have a moderate PI in the short term, but its long-term contribution to competitiveness and growth can be far more significant. PI does not capture these strategic benefits, which means projects critical for the organization’s future could be overlooked.

3. Misallocation of resources

If decision-makers prioritize projects only by PI rankings, resources may end up directed toward initiatives that look profitable on paper but do not maximize long-term value. For example, a series of small projects with high PI scores might collectively absorb significant funds, leaving insufficient capital for a single, larger project that could have transformed the organization’s capabilities. This misallocation reduces the efficiency of resource use.

4. Incomplete assessment of risk and timing

PI does not take into account the varying levels of risk or the timing of cash flows. Two projects may have identical PI values but very different profiles in terms of when returns are realized or how uncertain they are. For instance, one project could yield quick, low-risk returns, while another might involve high uncertainty and delayed cash inflows. Relying solely on PI could lead to treating these projects as equally attractive when they are not.

5. Need for complementary appraisal methods

Because of its limitations, PI should always be used in combination with other methods of investment appraisal. Net Present Value (NPV) provides insight into the total value created in monetary terms, Internal Rate of Return (IRR) shows the efficiency of returns as a percentage, and the Payback Period indicates how quickly an investment can be recovered. Using these methods alongside PI ensures that decisions are more balanced, capturing both financial returns and broader strategic considerations.

Read Also: Cash in Financial Accounting: The Lifeblood of Business

Disadvantages of Product Profitability Analysis

Product profitability analysis is a common tool that helps firms evaluate how much profit each product contributes to the overall business. While it can guide managers in deciding which products to promote, discontinue, or redesign, the method also has important limitations. These drawbacks stem from how costs are assigned, how shared resources are treated, and how non-financial factors are excluded. Understanding these disadvantages is essential for interpreting results correctly and avoiding decisions that might harm the company in the long run.

1. Neglect of Indirect Costs

One major limitation is that profitability analysis often fails to capture indirect costs. While direct costs such as raw materials and labor are relatively easy to assign to a product, indirect expenses like administrative support, marketing campaigns, distribution logistics, or maintenance are harder to allocate accurately. If these indirect costs are overlooked or spread too thinly across products, the analysis may paint an unrealistic picture of profitability. For example, a product may seem highly profitable when in fact much of the company’s overhead is being absorbed by it without proper recognition.

2. Oversight of Shared Resources

Another weakness lies in how shared resources are accounted for. Many companies operate with facilities, equipment, or staff that serve multiple products at once. In such cases, attributing costs precisely to individual products can be challenging. If these shared costs are allocated improperly, certain products might appear more profitable than they really are, while others seem less viable than they truly are. For instance, two product lines may share the same distribution network, but if costs are not split accurately, one product might be unfairly favored in the profitability report.

3. Exclusion of Brand Reputation and Long-Term Effects

Profitability analysis typically focuses on financial figures such as revenues and costs, but it does not capture broader, long-term impacts on the business. Some products might yield low short-term profits yet strengthen the brand, attract loyal customers, or open opportunities for future offerings. Conversely, a product that appears profitable in the short term might harm the company’s reputation if it fails to meet quality standards or creates environmental concerns. Ignoring these strategic and reputational effects can lead to misguided decisions, such as discontinuing products that build long-term value or continuing products that erode trust.

Assumptions of Profitability Index

The profitability index, while simple and widely used, rests on several underlying assumptions. These assumptions make the method easy to apply, but they also introduce potential weaknesses if the real-world situation does not match the theoretical framework. Understanding these assumptions helps learners and decision-makers recognize both the strengths and the risks of relying on PI for project evaluation.

1. Constant Discount Rates

The profitability index assumes that all future cash flows are discounted using a single, constant rate over the entire life of the project. In practice, discount rates are rarely fixed. They can fluctuate due to changes in interest rates, inflation, project-specific risks, or overall market conditions. For example, a project with higher risk in later years may require a higher discount rate for those cash flows, but the PI does not account for this nuance. By applying one uniform rate, the PI can oversimplify the financial environment, leading to either overvaluation or undervaluation of a project.

2. Reinvestment at the PI Rate

Another key assumption is that interim cash inflows can be reinvested at the same rate as implied by the project’s profitability index. This assumption is rarely realistic. Reinvestment opportunities available in the market may yield lower returns, especially if economic conditions shift or capital markets tighten. For instance, a project with a PI suggesting a high reinvestment rate assumes that cash inflows will continue to earn at that same rate, which often does not happen in practice. If reinvestment occurs at a lower return, the actual project value will fall short of what the PI initially suggested.

3. Accurate Cash Flow Projections

The profitability index depends heavily on the accuracy of estimated future cash inflows and outflows. If these projections are overly optimistic, the PI will show an inflated picture of profitability. Conversely, conservative or underestimated cash flows may discourage investment in projects that are actually viable. For example, a project in a volatile market may face sudden changes in demand, input costs, or regulatory pressures. Since PI cannot correct for errors in forecasting, it magnifies the consequences of flawed assumptions. This reliance on precise estimates makes PI highly sensitive to the quality of input data.

Read Also: Nurses’ Role in Healthcare Capital Budgeting

Why the Profitability Index Can Be Preferable to NPV

The profitability index (PI) and net present value (NPV) both use discounted cash flows, but they answer different questions. NPV measures absolute value created in currency units. PI expresses efficiency, showing how much present value is generated per unit of present value invested. That difference makes PI advantageous in some practical situations. Below are the main advantages, explained precisely and with brief context so a learner understands when PI is the better choice and what caveats to watch.

1. Fast, easy screening of many projects

PI is quick to compute and easy to compare across a long list of proposals. When an organization needs to triage a large number of small or medium projects, PI provides a simple filter to find proposals that yield the most value per unit invested. This makes PI useful for initial screening before applying deeper analysis with NPV or other techniques.

2. Better guidance under capital rationing

When available funds are limited, managers must choose the combination of projects that maximizes value for a given budget. PI ranks projects by efficiency, which helps select projects that give the highest return per unit of capital. In such constrained settings PI often produces more useful shortlists than NPV, which prefers larger absolute gains that may not fit the budget.

3. Normalizes projects of different sizes for direct comparison

Because PI is a ratio, it puts projects of different scales on a common basis. That helps when decision-makers want to compare the proportional profitability of investments that otherwise are not directly comparable. The normalization is helpful for evaluating proposals that compete for the same pool of capital but differ greatly in scale.

4. Intuitive interpretation for non-technical stakeholders

PI states in simple terms how much present value is created for every unit invested. That clarity can help managers, board members, or investors who prefer a single, easy-to-communicate metric when making initial decisions or explaining choices.

5. Useful when combining multiple small projects

When a firm can fund several small projects instead of one large investment, PI helps identify which set of small projects, taken together, will produce the best return per unit invested. This makes PI a practical tool for portfolio selection of multiple, discrete initiatives.

Important caveat

PI’s strengths arise from its ratio form. That same feature can bias decisions toward smaller projects with higher relative returns but lower absolute value. For example, a small upgrade with a PI of 1.5 may look more attractive than a large factory expansion with a PI of 1.2, even though the factory project produces far more total NPV. Use PI for screening and ranking, but confirm final selections using NPV or other absolute-value measures.

Conclusion

The profitability index remains a useful metric for preliminary screening and relative comparisons of projects, thanks to its simplicity. However, its disadvantages, including neglect of scale, timing, cost of capital, and non-financial considerations, mean that it should not be the sole basis for investment decisions. A comprehensive evaluation that combines PI with other financial and strategic tools provides a more accurate and balanced foundation for selecting projects that maximize value.

Comments are closed!